Sustainable Livestock

Meat, and particularly beef, has been in the spotlight recently for its contribution to global warming mainly because of methane (not carbon dioxide) that cows and sheep produce when they digest their feed.

But, like many things, it’s not a black and white picture and, from an environmental perspective, a cow in Brazil is a very different animal to a cow in Britain.

It’s a fact that methane is a greenhouse gas. But, unlike carbon dioxide which once produced, stays in the atmosphere forever, methane breaks down after around ten years. Levels of methane emissions are comparatively low in the UK with sheep and cattle production responsible for 5.7% of the total greenhouse gas emissions . This is much lower than the average global figure of 14% that most often gets quoted in the media but which includes environmentally un-friendly farming systems in countries like Brazil.

That 5.7% of UK emissions is further reduced to a net 3.7% by the fact that British cattle and sheep are grazed on permanent pasture that acts as a ‘carbon sink’ where the grass sucks carbon dioxide out of the air to grow more grass and store the excess CO2 in the soil. And, our farmers are working to reduce that even further through innovative breeding and feeding initiatives.

Will giving up meat save the planet?

Virtually everything we humans do has a carbon footprint and we’re all now facing a choice about which aspects of our personal lifestyle to change in order to save the planet.

But there’s a problem. Most people rely on information in the media to help them make those choices. But not all that information is correct. In fact, some of it is quite misleading.

It’s become very difficult to navigate the confusing and often contradictory opinions, pseudo-science and genuine science in the media that are currently shaping ordinary people’s choices about what they should and shouldn’t be eating.

Findings from scientific studies can be misinterpreted or taken out of context to suit a particular argument and this can quickly turn into a global news headline, with meat often getting blamed for everything from cancer to climate change.

When it comes to making decisions about our diet and nutrition, which could have big implications for our health, we should be able to have a balanced debate, not a one-sided argument about the contribution that meat and livestock has to climate change.

If we oversell the idea of a meat-free diet as the solution to climate change, we risk increasing the damage from intensive, chemical-reliant arable farming, which can be just as destructive.

Also, removing two major food groups (meat and dairy) from people’s diet could have huge unintended consequences for public health with a consequent burden on health services. This is because there are essential nutrients that can only be found in animal products and the often highly processed plant-based substitutes don’t provide an adequate alternative source of these nutrients.

People run the risk of unwittingly switching from a healthy balanced diet to a less healthy diet that both lacks essential nutritional elements and has been less sustainably produced.

British meat is part of the solution

The solution to both climate change and the need to feed a global population of nearly 10 billion people by 2050 will require a balanced approach.

This will include eating less meat, as well as choosing meat that’s been sustainably reared. It will also require us to develop less intensive, more innovative ways to farm food, coupled with the adoption of new technologies. We should also strive to reduce the £3 billion worth of meat we waste every year, mainly from our own fridges. You can read more about this on the WRAP website.

If we want to make meaningful changes to how we live in order to help the planet, then we need to base our decisions on information that is accurate and specific to our situation here in the UK. If British people give up British meat and dairy and replace it with commercially produced meat-alternatives, they will not get the environmental benefit they had hoped for.

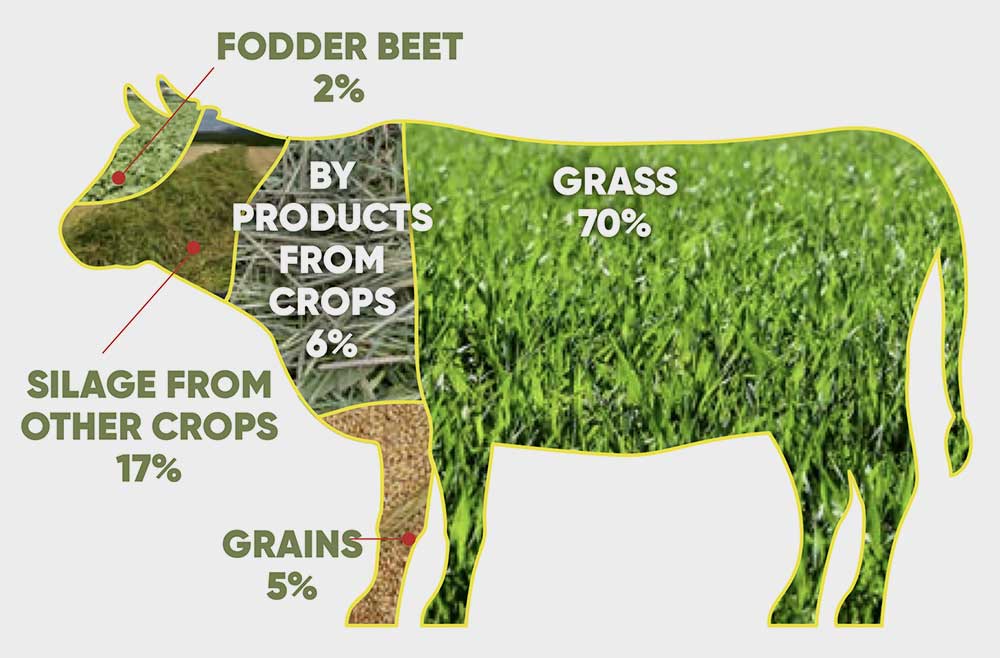

Our farmers work with what nature has given them, turning grass and rain into one of the most nutrient-dense foods you can buy. They graze their animals on what’s called ‘marginal grazing land’ which can’t support other types of agriculture because the soils are too poor. In fact farmers can enhance the carbon sequestration of their grasslands through grazing management and sowing the right kinds of forage species. That’s very different to how meat is produced in other parts of the world that rely on clearing rainforest to create intensive feedlots.

Very often this distinction is not made in the media when discussing climate change and dietary choices.

A world without livestock

Currently 600,000 British people (less than 1%) eat a vegan diet. The vast majority get their nutritional requirements from a mix of meat and plants. The question we have to ask is: what effect would it have on the planet if all 66 million people were to give up meat and dairy and, instead, rely on plant-based foods?

We already import 47% of the foodstuffs we consume here in the UK. If we were to try and feed the entire population with non-meat or dairy substitutes (things like soy and nut milks for example) which we don’t grow here, what pressure would that put on the world’s arable land? How would soil health and biodiversity be affected if we were to switch to the type of chemical-reliant monoculture that would be needed to replace the nutrition we get from meat and dairy?

The UK land vacated by livestock certainly wouldn’t support growing any other type of food so we would be removing a large amount of land from our local food production system at a time when our population continues to grow.

Giving up eating British meat will be of much less environmental benefit than giving up eating Brazilian meat. And, substituting British meat for a more environmentally damaging processed plant-based alternative could even have the opposite effect.

Consider this statement from Dr Trevor Dines, Botanical Specialist from Plantlife, on the publication of research showing that meadows face mounting risks from poor legal protection, and from land abandonment and undergrazing, July 2019:

“habitats like hay meadows and permanent pastures, grazed by the right amount of livestock at the right time, can support an astonishing 770 species of wild flower and are crucibles of biodiversity. Nearly 1,400 species of pollinators and other insects rely on species-rich grassland for their survival and they, in turn, support a myriad of bird and animal life. Re-creation of these open habitats must be seen as a priority as urgent as planting trees.”